ILCs: Fad or the Future?

Resurgence of rare charter may reshape the banking industry

The FDIC has two decisions to make that will have a tremendous impact on the financial services industry. On June 6, online personal finance company Social Finance, Inc.* (better known as "SoFi") applied for an industrial loan charter (ILC) for the purposes of offering FDIC-insured NOW deposit accounts and credit card products—this in addition to the student loan refinancing, mortgages, and personal loans the company already offers its customers. The de novo would be chartered in Utah under the name SoFi Bank. On September 7, payments giant Square filed its application** for a Utah-based ILC for the purposes of expanding its lending arm—in addition to payments, Square also offers small business and consumer loans. While (at the time of this writing) the FDIC has yet to take action, approval or denial of these applications will set the stage for the next phase of bank-fintech relations.

Historical Context

Now state-chartered companies operating with federal deposit insurance, the ILC business model has been in existence since the early 1900s. Since their inception, non-bank retail companies have used these entities primarily to make consumer finance loans in order to sell their products, explained Attorney James Sheriff, partner at Reinhart Boerner Van Deuren, s.c. For example, BMW, General Motors, and Target all had industrial bank subsidiaries (and some still do). "The charter allows commercial companies to own financial institutions that can take federally insured deposits," explained Attorney Patrick Neuman, partner at Boardman and Clark, LLP. This bucks the long-standing policy in the U.S. to separate commerce and banking, a policy created in 1933 by the Glass-Steagall Act and reinforced by the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 (BHCA).

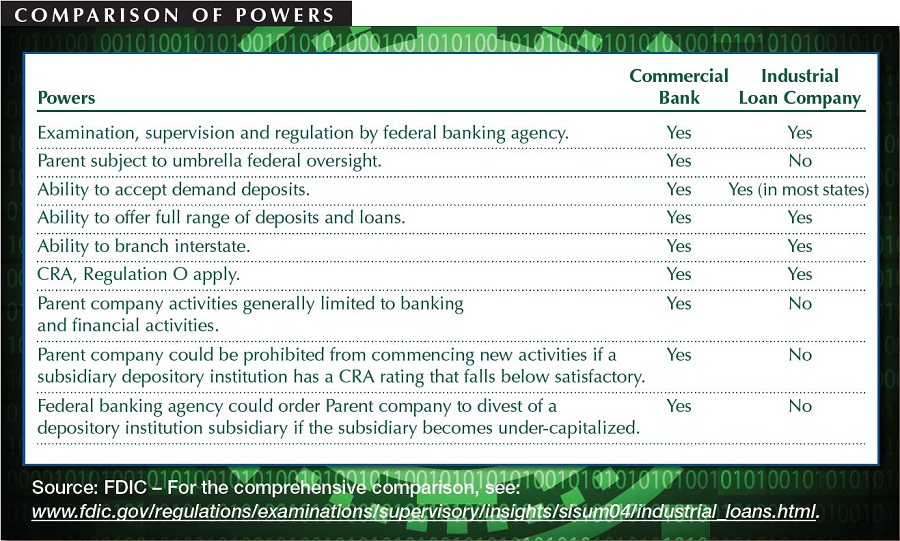

Only seven states currently have provisions allowing for ILCs: California, Colorado, Minnesota, Indiana, Hawaii, Nevada, and Utah (where the vast majority of industrial banks are headquartered). Due to their exemption from the BHCA, ILCs are regulated only by their chartering state regulator (the Utah Department of Financial Institutions oversees ILCs with over $143 billion in combined assets) and the FDIC. The Federal Reserve has no authority to regulate the activities of the parent company, which—unlike traditional charters—is not limited to activities that are substantially related to banking.

However attractive this charter may seem, it has not been a popular option in recent years. No ILC applications were filed between 2009 and SoFi's application in June 2017—a timeframe which includes a three-year moratorium imposed by the Dodd-Frank Act (lifted in 2013). The last company to garner attention for its ILC application was Walmart in the mid-2000s. Fearing the retail juggernaut's entry into retail banking, the banking industry successfully lobbied for laws in several states (including Wisconsin) prohibiting ILCs from having a banking facility within 1.5 miles of a retail location owned by the same parent company. At the time, it was considered a great success. However, today's applicants aren't interested in physical retail locations. "Before, the goal was to bring consumers into the store in order to win their banking business," Sheriff explained. "Today, the brick-and-mortar isn't important, but rather wanting to expand financial products and services. It's a different threat."

Renewed Appeal

The current financial services landscape is ripe for renewed interest in ILCs. Technological advances have made brick-and-mortar branches unnecessary and nation-wide reach attainable. However, banking's regulatory structure has not kept pace with the change. "Right now, in order to be a financer these companies need to get licensed in all states they do business in," Sheriff explained. One of the biggest attractions of an ILC is the federal pre-emption it offers. "Instead of 50 state regulators examining your consumer finance company, there's one state and the FDIC," he said.

Another major draw of an ILC is that it allows the parent company to retain the flexibility to experiment that fintech startups are known for. "SoFi is a tech company and doesn't want to be hamstrung by the Bank Holding Company Act," said Neuman. "ILCs are not subject to consolidated supervision at the holding company level. That's a big advantage."

Operationally, fintech companies like SoFi and Square would receive another important benefit from obtaining an ILC: a stable funding source. "Both companies make loans, and if they get an industrial loan charter they get access to federally insured deposits. Deposits are a significantly less expensive source of funding than investment capital or bonds," Neuman explained. The availability of government-backed deposits as a funding source would alleviate concerns over whether institutional funding is stable enough to weather an economic downturn or significant market fluctuation.

What Happens If…

FDIC's approval of either pending ILC application would have profound implications for the future of the financial services industry. "If the FDIC decides to approve one of those applications, it could be a game-changer," said Neuman. "If either application is approved, there will be a flood of new applications." If SoFi or Square does receive an ILC, the banking industry will need to prepare for several long-term effects.

First is a new, aggressive source of competition. "The most often-cited concern with ILCs is that they could lead to a concentration of economic power in banking," said Neuman. With ILC charters, giant technology retail companies like Apple, Amazon, and Google could offer the same products to consumers as banks. "They'd be behemoths to deal with in a consumer or small business banking sector," said Sheriff. In addition, those companies' data collection activities would not be restricted by the BHCA, enabling them to obtain and analyze consumer data that is not available to most banks. "That could seriously undermine a bank's ability to compete," said Neuman. One area where the competition could be especially fierce is in small business lending. "If the ILC option becomes more popular, and if small fintech lenders like Prosper get these charters, it would create a lot more competition for community banks in small business lending," said Sheriff. "It has some real potential detriments for community banks."

Another concern directly relates to SoFi's business model, which is driven by a focus on HENRY customers (High Earner Not Rich Yet). "Much of their business is student loan financing for professionals such as doctors and lawyers. There's concern in the industry that fintech lenders won't adequately serve the working class household or be able to meet CRA requirements," Neuman explained. "This type of business model could lead to a disproportionate allocation of credit." Banks can only speculate how the state regulators and FDIC will address CRA concerns with ILCs.

Increased popularity of ILCs may also dampen partnerships between banks and fintech companies—partnerships that currently expand product and service offerings for many bank customers. "If FDIC starts approving these charters, there will be fewer partnerships between fintechs and banks," said Sheriff. "The fintech companies will no longer need to partner in order to get data and deposits." This is not conjecture. Former SoFi CEO Michael Cagney told TechCrunch the company plans to offer checking, deposit, and credit card services through a regional banking partner if the ILC application is not approved.

Finally, ILC opponents see increased risk to the industry as a whole if these charters have a resurgence among technology companies. "What happens if one of these goes through and becomes huge, but then the parent company makes some wild bet and goes under? That could be a huge hit to the FDIC and the banking industry in general," Sheriff said. "Bank regulators aren't familiar with how to evaluate some of those widespread risks. We've separated banking and commerce for 85 years for a reason." The same concern applies to the potential for further increasing the market power of the "Big Five" (Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft) by adding banking services to their already diverse lines of business.

What if the FDIC denies the pending applications? Will community banks be able to breathe a sigh of relief and go back to business-as-usual? Probably not. "If these fintech companies don't get approval for an ILC, I believe they'll pursue other avenues, such as an OCC fintech charter," said Neuman. "Banks are going to see fintech as a real competitor in the lending space, and sooner rather than later." Influencer companies in the technology sector have set their sights on banking products, and they won't be easily deterred. "The bottom line is that there is activity in this area right now," said Sheriff. "This isn't hypothetical."

Boardman and Clark, LLP is a WBA Gold Associate Member.

Reinhart Boerner Van Deuren, s.c. is a WBA Associate Member.

*View a copy of SoFi's application here. On October 13, SoFi withdrew its application for an ILC charter as it undergoes a leadership transistion, but says "a bank charter remains an attractive option."

**Square's ILC will be named Square Financial Services, Inc., according to a Wall Street Journal report.

By, Amber Seitz