Photo taken in Clinton, Wis. by Debra Hall, First National Bank and Trust Company

By Paul Gores

Many Wisconsin farmers are headed for a profitable year, but they’re already uneasy about 2023, ag bankers in the state say.

Coming off a strong 2021 that saw rising dairy and commodity prices, farmers entered the year financially fit and, in many cases, with locked-in input expenses that have blunted 2022’s surge in inflation.

But with the cost of fertilizer and diesel fuel ballooning, and livestock feed for those who don’t produce their own feed becoming more expensive, it’s hard to see how the next growing season can be as solid as this one has been so far, bankers said.

“I think there’s more anxiety about what next year looks like than there is over what this year looks like right now,” said Dave Coggins, senior vice president ag banking for Green Bay-based Nicolet National Bank.

With diesel fuel now topping $5 a gallon, and with fertilizer prices up in part because key ingredients come from embattled Ukraine and Russia, input costs are increasing.

“A number of farmers were able to contract prices last fall and early winter before they totally took off and escalated. So some of them have fuel locked in for this year less than $3,” said Jenny Jereczek, director of ag banking for Security Financial Bank in Durand. “So they’re doing all right for this season. What I’m hearing and seeing and in talking with people is 2023. Right now, there is not really a good opportunity to contract good pricing for next year, and will there be? No one has the crystal ball.”

Bradley J. Guse, senior vice president/agribusiness banking for BMO Harris Bank in Marshfield, said many farmers, coming off a good 2021, are having a strong 2022 in spite of the rocky economy. He cited record crop prices in the first three months of the year, when prices typically are low, and the benefit of farmers growing their own feed.

“In Wisconsin, we grow a lot of our feed. That’s a big advantage to our Wisconsin dairy guys,” Guse said. “Because of that, they are feeding feed that they grew last year now, and last year’s cost to grow was a lot cheaper than this year. So we’ve got low feed prices because we grew cheaper last year, and we’re running the into these high milk prices. And we’re seeing margins that are just phenomenal.”

Milk has been selling for about $25 per 100 pounds, hovering near record levels.

But he, too, is concerned about next season.

“I’m not so worried about my clients and my portfolio this year as I am next year,” Guse said.

Ag bankers said international events and circumstances often set the stage for prices farmers pay to produce their goods and the prices they get at market.

“There was a drought in South America, a pretty serious one. That’s impacted crops — corn, soybeans — that are big crops in South America, especially soybeans,” Coggins said. “So we’ve got really high soybean prices in part because of that. But also, the war in Ukraine has had a serious impact on supplies of grains in general, but basically corn, wheat, barley, sunflower oil. Russia exports a fair amount. Ukraine exports a fair amount. I think the Black Sea region produces about 12% of the world’s calories, and so that’s a big deal.”

That affects the availability of those grains and pushes up the price. In Wisconsin, that means dairy farms that buy their feed pay more. But, in turn, it provides higher prices for the state’s grain producers.

What happens in the Black Sea region also has an impact on fertilizer prices. Coggins said 47% of the world’s phosphate and potash, which are used in fertilizer, come out of Russia and Belarus.

“There’s not a lot of other alternatives for getting that fertilizer. Most farms were in OK shape this year. Might have been able to lock in some prices late last fall or winter,” Coggins said. “But there is a lot of anxiousness about what those prices and availability might look like for 2023.”

The rise and fall of energy prices also is an inescapable fact of life for farmers. According to the Diesel Technology Forum, diesel engines power about 75% of all farm equipment, transport 90%

of farm products, and pump about 20% of agriculture’s irrigation water in the U.S.

Lance Lansing, vice president-commercial and ag loans for Wisconsin Bank & Trust, said the price rise with diesel fuel is mostly a refining capacity issue.

“Investors don’t want to put new refineries up right now,” said Lansing, who works out of Monroe and Platteville. “With electric cars coming out, nobody’s running to put new refineries up and have that sort of investment, not knowing what their return’s going to be.”

Lansing described the current farm economy as “volatile.”

“There’s a lot of moving parts. One saving grace is we have had good commodity prices. The milk price has obviously been up, and futures still look good. Same with the row crops. The row crops are still looking good, and a lot of people are locked in at a profit in 2022,” Lansing said. “2023 might be a different story.”

Although there is worry about next year, many farms today are in a good position financially, Jereczek said. But they are being cautious.

“At least in this area, we’re seeing some expansion, but maybe not like we’ve seen in the past when commodity prices have gotten to these levels,” Jereczek said. “I think farmers and bankers alike are more strategic this go-round, and have learned a lot from the past in regards to now is the time for improving leverage positions, paying down debt, paying down lines of credit and maybe stacking some cash away in savings for liquidity purposes, and those kinds of things.”

Still, some are making strategic equipment purchases they delayed when finances were tighter four or five years ago, she said.

Lansing said he isn’t seeing many farmers interested in spending to expand herds or land right now, even though commodity prices are high.

“I’m just a small section of the state here, but a lot of people aren’t reinvesting as far as in growth mode. They are more in, ‘Let’s find out what’s going to happen, pay down debt, right-size debt type’ mode,” Lansing said.

Higher interest rates might be dampening some spending by farmers, but it’s hard to say how much.

“I think the interest rates are maybe a little bit inhibiting some of that stuff,” Jereczek said.

But she said a lot of operating lines already were done over the winter and early spring.

“So they are not necessarily impacted by the rate increases we’ve see more recently,” Jereczek said.

Ag bankers said crop conditions generally look good around the state, but rain will be needed in early August.

“Rain in July makes corn, rain in August makes beans,” Guse said.

Coggins said it appears soybeans are likely to be a winning crop this year.

“Soybeans are really at all-time highs for price right now, in large part because of what happened in South America,” he said. “And the input costs of soybeans are less than corn, so that’s a crop that has the potential to be a winner this year, absent any major weather events.”

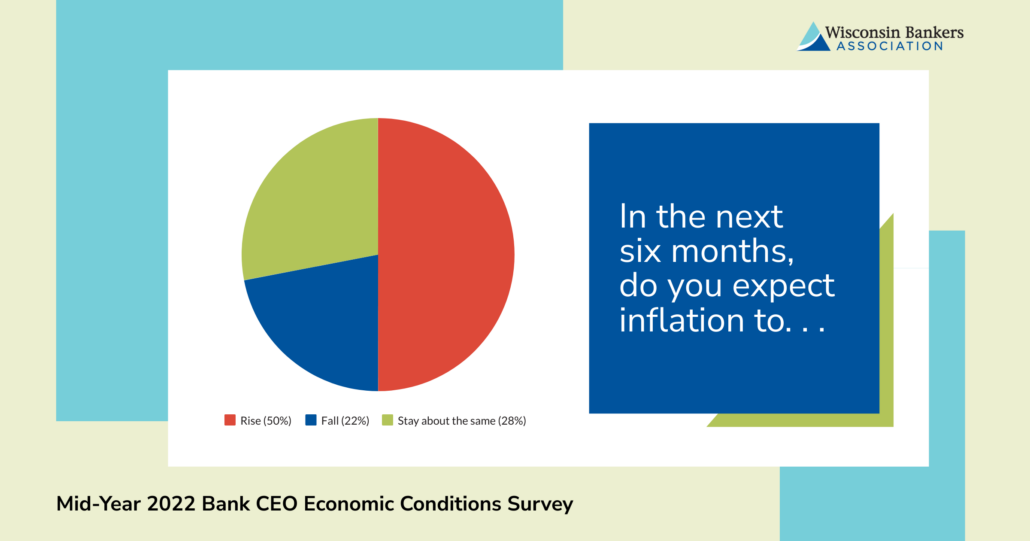

As for how farmers fare next year, much will depend on inflation and its upward pressure on input expenses, ag bankers said.

“Financing of inputs for next year could be a completely different story,” Jereczek said.

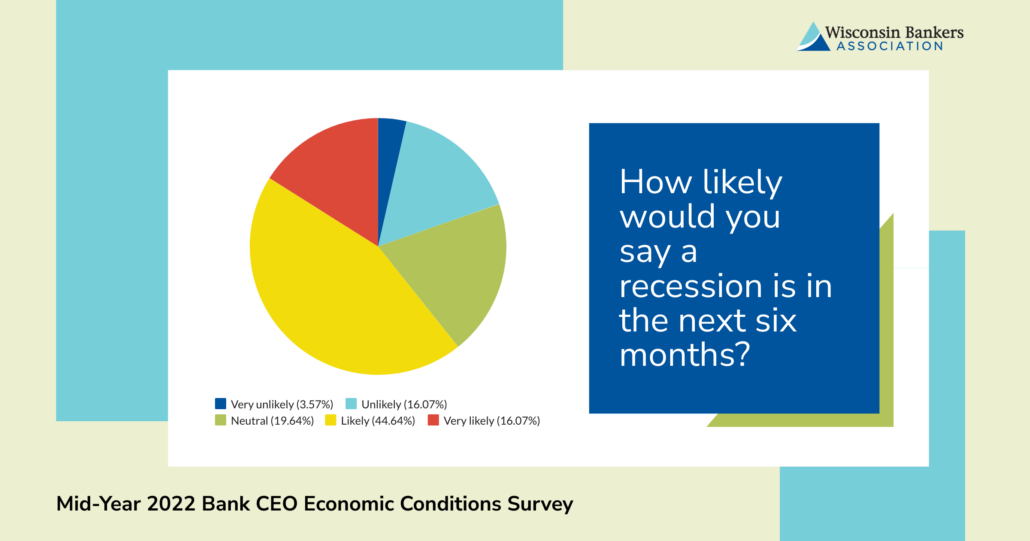

A recession might also be looming. While demand for Wisconsin farm products is high right now, a recession could change the outlook.

“I think every ag banker right now is worried about a recession destroying that demand,” Guse said. “I think we’re all concerned about that — what’s on the horizon.”

Gores is a journalist who covered business news for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel for 20 years.