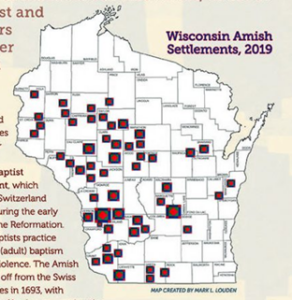

Serving Amish and Mennonite Communities in Rural Wisconsin

Map created by Mark L. Louden

By Cassandra Krause

The Amish may not be the first group to come to mind when thinking about the fastest growing populations in the United States (and even the world), however these communities — whose populations double about every 20 years — play an important role in rural America, especially in Wisconsin. The Amish trace their heritage on this continent back about 300 years, when a small group of settlers immigrated to colonial Pennsylvania. According to the Max Kade Institute for German American Studies, today, there are approximately 350,000–400,000 Amish in North America (none remain in Europe), with more than 21,000 calling rural Wisconsin home. Wisconsin has the fourth-largest Amish population among 32 U.S. states and four Canadian provinces. Wisconsin also has a population of approximately 5,000 Old Order Mennonites as well as smaller numbers of other Mennonite groups and Old German Baptist Brethren. These groups are collectively described as Plain people, referring to their plain style of dress. Plain communities add to Wisconsin’s diversity and are familiar faces at many community banks.

Who Are the Amish and Mennonites?

Dr. Mark Louden, professor of German linguistics at UW–Madison and director of the Max Kade Institute, is a leading expert on the language and culture of Amish and Mennonites. He explains that Amish and Mennonites are Anabaptist Christians who practice believer’s baptism (babies are not baptized; rather, members formally join the church as teens/young adults) and are nonresistant, meaning that they do not engage in violence, including serving in the military. Old Order Mennonites and Amish wear modest, traditional clothing as an outward expression of humility. Women wear simple dresses and a veil, also called a prayer covering or kapp, over their hair. A larger bonnet is something that may be worn over the veil. Men wear solid-colored shirts and suits with wide-brimmed hats. The degree to which Plain people limit the use of technology depends on the group — as is the case in mainstream American culture in which some people may, for example, limit screen time or opt for a paper calendar rather than a digital one. Most Amish groups do not have electricity in their homes and do not own or operate motorized vehicles.

Farming and Beyond: Economic Activity

Plain people are active in a number of areas of the economy. The percentage of Amish families that depend on agriculture as their main source of income is only around 10–15% nationally, however, Amish and Old Order Mennonites live in rural areas and typically have large gardens. Businesses commonly owned by Plain people include carpentry — especially in Wisconsin where lumber is abundant — construction, and retail stores selling quilts, crafting supplies, bulk food, and baked goods. Outside of Wisconsin, some Amish are employed by non-Plain-owned businesses such as factories.

Finances in Amish and Mennonite Communities

Amish and Mennonite communities practice mutual aid, which sometimes involves assisting each other financially. Amish do not purchase commercial insurance or accept government assistance, so when there is a special need, the community steps in to help. They also do not typically take out loans other than mortgages for property, especially farms. Business loans are very uncommon, as the types of businesses Amish run are generally relatively small and do not require large amounts of capital to start up or grow. Amish farmers also do not use the types of equipment that other farmers may borrow larger sums for. Louden notes that “Amish and Mennonites are known for being extremely good customers. . . bad debt is hardly a concept.” He adds that if, in a rare instance, somebody were unable to pay their mortgage, the community would likely step in to, “not necessarily give them a lot of fish, but teach them to fish,” in order to help them with their money management and get them back on their feet. Louden emphasizes that financial responsibility is important in Amish and Mennonite culture.

Louden said that a misunderstanding persists that the Amish do not pay taxes, when they do, in fact, pay income and property taxes. The only exception has to do with Social Security and Medicare taxes. Members of Amish, Old Order Mennonite, and other churches who decline any form of government assistance may apply for an exemption from Social Security and Medicare withholding by filing IRS Form 4029.

Tips for Best Serving Amish and Mennonite Customers

“Small scale and face to face is preferred” when it comes to banking Amish and Mennonite customers, Louden explains. “Folks who work in banks in small communities in proximity to Amish and traditional Mennonites get to know their Amish and Mennonite customers well and see them a lot because they’re coming in there. . . they’re even using the drive through windows with their horse and buggy.” He said that there aren’t really special accommodations bankers need to make for their Amish and Mennonite customers; just treat them in the same friendly manner they do for any other customer. Amish and Old Order Mennonites are fully bilingual in Pennsylvania Dutch and English, so translation is not needed.

Having a hitching rack available for parking is considered a best practice for banks and other businesses (e.g. Walmart, Costco, etc.) that serve Amish customers. A 2021 Banking Dive article highlights how a community bank in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (home to one of the largest Amish populations), took an even more creative approach. The Bank of Bird-in-Hand debuted their first “gelt bus,” which translates from Pennsylvania Dutch to “money bus,” for mobile banking in 2018. They now offer a fleet of bank branches on wheels to visit their Amish customers.

Amish and Mennonites tend to use checks most frequently and will balance their checkbooks by hand. They will use debit cards, and many will use credit cards; paper statements in the mail are usually preferred.

Photo identification may be a topic banks need to navigate, as many Amish do not like to have their photo taken due to religious belief. “Banks are required by law to establish a reasonable belief as to the true identity of their customers,” notes Scott Birrenkott, WBA director – legal. “Fortunately, the law does give some flexibility. In that regard, a bank working with Amish customers should consider how their policy is tailored given the unique lifestyle of the Amish.”

Sheila Kast, BSA Officer, AVP at Horicon Bank, explains that their bank’s Amish customers do have Social Security numbers and cards. For their Amish customers in the Kingston area, their deposit and loan operations team will verify the customer’s name in the Kingston Amish Directory. For verification of identification, Horicon Bank requires at least two of the following documents:

- Social Security Card (required)

- Property Tax Bill

- Tax Document/Tax Return

- Marriage Certificate

- Birth Certificate

- Fishing/Hunting License

On the lending side, banks may find that mortgages for Amish customers necessitate unique procedures since they do not have electricity or carry insurance. A lender may find difficulty working with investors if the borrower is unwilling to obtain homeowners insurance, requiring a tailored risk management approach. Birrenkott explains that some banks may have policies tailored to working with Amish borrowers. For example, Horicon Bank has indicated that policies from the Amish Aid (a non-profit alternative to commercial insurance) are accepted for insurance. The issue of flood insurance may offer less flexibility, however, because if the property is in a flood zone, Federal law requires flood insurance with no exception due to religious belief.

A Look Ahead at Wisconsin’s Rural Communities

As Wisconsin experiences shifting demographic and migration trends — particularly outmigration from rural areas as younger people flock to urban and suburban areas — it is important to recognize the role of the growing populations of Plain people in rural communities. Amish, for example, have on average six to seven kids per family, approximately 85–95% of

whom formally join the church as young adults, depending on the group. This is notable, as national trends show younger Americans identifying less and less with formal religion. Data from the Pew Research Center in 2015 showed the highest retention rates for Millennials were among Jews (70%) and those raised unaffiliated with a religion (67%), followed by those raised in the evangelical Protestant (61%), historically black Protestant (60%), Catholic (50%), and mainline Protestant (37%) traditions.

Plain people are woven into the fabric of their rural communities. As such, they play an integral part in the past, present, and future vitality of Wisconsin.